Wednesday, the 17th July:

For this day, we had booked tickets for a cruise ride at Whittier, 88 miles away from Seward (and 60 miles South of Anchorage). Whittier sits at the head of the Passage Canal. We drove back on the Seward highway until we reached Turnagain Arm of Cook Inlet and then into Portage glacier road. There is a 2.5 miles long Anton Anderson Memorial railroad tunnel (locally known as the Whittier tunnel or Portage tunnel), through the Maynard Mountain hills, just before Whittier.

· Vitus Bering, a Danish navigator who served in the Russian Navy and who discovered Alaska in 1741,

· George William Stellar, the famous German Naturalist, a member of the Bering Expedition, which made landfall at Kayak Island, approximately 100 miles southeast of Whittier. Many living species are named after Stellar: Stellar Sea Lion, Stellar Jay, Stellar Eider and Stellar Sea Eagle, and

· Capt. James Cook who entered the Sound on May 12, 1778. While he traded with the area’s indigenous people, William Bligh – later of the Mutiny of the Bounty fame – took a small boat and paddled long enough to determine it was not the Northwest Passage. It was Bligh Reef that the Exxon Valdez struck in 1989.

1) Tidewater Glaciers: Pressured by their own weight, active tidewater glaciers move toward the water, ending at the ocean’s edge where they frequently ‘calve,’ shedding slabs of ice that crash into the sea. These floating icebergs are so heavy that only the very tip is visible.

2) Piedmont Glaciers: These glaciers rest at the base of the mountain. They are formed when glacial ice forms a fan-shaped mass at the foot of the mountain range.

3) Alpine Glaciers: Also known as hanging glaciers, these ice masses start high on the slopes of mountains, and literally ran from the mountainsides.

For this day, we had booked tickets for a cruise ride at Whittier, 88 miles away from Seward (and 60 miles South of Anchorage). Whittier sits at the head of the Passage Canal. We drove back on the Seward highway until we reached Turnagain Arm of Cook Inlet and then into Portage glacier road. There is a 2.5 miles long Anton Anderson Memorial railroad tunnel (locally known as the Whittier tunnel or Portage tunnel), through the Maynard Mountain hills, just before Whittier.

Whittier tunnel, along with the port at Whittier, was built as a military

facility during the Second World War by the U.S. Army. It is the second longest

highway tunnel, and longest combined rail and highway tunnel, in North America.

It links the Seward highway south of Anchorage with Whittier and is the only

land access to the town. The tunnel is named after the army engineer who

supervised construction of the rail spur through Maynard Mountain. The

tunnel is a critical bottleneck. It allows traffic to flow from one side to the

other, allowing 15-minutes slot for the vehicles and another 15-minutes slot

for the train. That meant, once in an hour, you got a 15 minute slot to cross

through the tunnel. We couldn’t afford to be late, so we had started from our

hotel at Seward quite early and we were there in front of the tunnel just five

minutes before the suggested 10.30 AM slot for our crossing-over.

Whittier is just a small port town with a population

of less than 300 most of who stay in one big building. The spur of the Alaska

Railroad to Camp Sullivan, as the place was originally named by the army, was completed

in 1943 and the port became the entrance for U.S. soldiers into Alaska. The port

remained an active army facility until 1960. The two huge buildings that

dominate Whittier were built after World War II. The 14-story Hodge building,

now known as Begich Towers, was

built for housing solders and the Bucker

Building, completed in 1953, was called the ‘City under one roof.’ Both

these buildings were at one time the largest buildings in Alaska. The Begich

building is now a condominium housing nearly all the Whittier’s residents.

Whittier was incorporated in 1969. Tsunamis triggered by the 1964-Good Friday Earthquake severely

damaged the town, including the now abandoned Bucker Building. Whittier is a

popular port of call for cruise ships. Whittier is also popular with tourists,

sport fishermen and hunters. The Whittier

Glacier near Whittier was named for the American poet John Greenleaf

Whittier in 1915.

We boarded the 12.30 PM 26-Glacier

Cruise. The cruise ship, we were told, would help us explore glacier carved Fjords, ancient ice and towering

mountains of the Chugach National Forest.

A quick reference to Google described a Fjord (pronounced as F’eord – the

letter ’j’ being silent, also spelled as ‘fiord’) as: “a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created in a valley

carved by glacial activity.” I learn that the coasts of Norway, Iceland and

Greenland have many fjords.

Some more interesting information

about Whittier: Long before

Westerners arrived, Chugach Eskimos,

now known as Alutiq, crossed the pass that separates Prince William Sound from the Cook Inlet’s Turnagain Arm in search

of fish, almost 7000 years ago, as the glaciers began to retreat. Miners later

took the route to reach the gold fields of Turnagain Arm. In Geography, a Sound

or Seaway is “a long, relatively wide body of water, larger than a strait or

channel, forming an inlet or connecting two large bodies of water, such as two

seas, or a sea and a lake.” The Chugach Eskimos were water people whose lives

centered on hunting and fishing. The Eyak,

who shared the Sound, were people of the shore who came from Alaska’s Interior.

These early people created small villages and lived in wooden houses. They made

clothing from sea otter and seal, wove baskets from grass and spruce roots and

used stones, bones, wood and shells to make tools. Today, about 1000 Alaska

Natives live in the Sound where their lifestyles range from traditional

subsistence to leading major Alaska Native-owned corporations.

Some of the greatest explorers who visited the Sound include: · Vitus Bering, a Danish navigator who served in the Russian Navy and who discovered Alaska in 1741,

· George William Stellar, the famous German Naturalist, a member of the Bering Expedition, which made landfall at Kayak Island, approximately 100 miles southeast of Whittier. Many living species are named after Stellar: Stellar Sea Lion, Stellar Jay, Stellar Eider and Stellar Sea Eagle, and

· Capt. James Cook who entered the Sound on May 12, 1778. While he traded with the area’s indigenous people, William Bligh – later of the Mutiny of the Bounty fame – took a small boat and paddled long enough to determine it was not the Northwest Passage. It was Bligh Reef that the Exxon Valdez struck in 1989.

That day’s 145-miles journey on

the cruise aboard the largest, fastest catamaran in Alaska took us through

rugged wilderness, towering glaciers and pristine waters.

Prince William Sound is 2100 square miles of islands and fjords,

carved by 15 million years of glaciations and surrounded by the Chugach

National Forest. It is America’s largest intact marine ecosystem and North

America’s northern-most rain forest. It

is also one of the most active seismic regions in the world. The journey took

us near the epicenter of the 1964 Good Friday earthquake that measured 9.2 on

the Richter scale.

From Whittier, the cruise headed

east through Passage Canal to the Egg Rock sea lion rookery in Port

Wells. We continued to scenic Esther

Passage where only small ships can navigate. High mountains protect this

narrow channel from rough seas and winds. Many animals call this area home.

Bald eagles are frequently seen fishing. Orcas are common and sea otters are

almost always present. Beyond Esther Passage, the vessel headed north in College Fjord, a glacier-rich region

whose namesake came from a science expedition led by American railroad

financier Edward Harriman. The team

named each glacier along the northwest side of the fjord after prominent

women’s colleges, while those on the southwest side were named after men’s

colleges. Next we cruised to Barry Arm

and Surprise Glacier in Harriman Fjord. The cruise plotted a

path through the ice-filled waters up to the front of the glacier so we could

watch for ice calving into the sea. The ship made the last stop at the kittiwake bird rookery just across the

bay from Whittier. It is reported that more than 10000 birds inhabit these

rocky cliffs each summer laying eggs, fishing and teaching young hatchlings the

survival tips they will need before they fly south for winter.

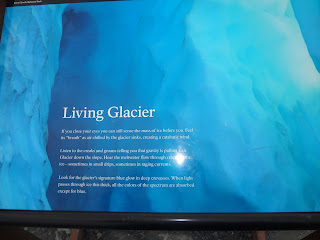

Our routes took us past three

types of glaciers found in Alaska: 1) Tidewater Glaciers: Pressured by their own weight, active tidewater glaciers move toward the water, ending at the ocean’s edge where they frequently ‘calve,’ shedding slabs of ice that crash into the sea. These floating icebergs are so heavy that only the very tip is visible.

2) Piedmont Glaciers: These glaciers rest at the base of the mountain. They are formed when glacial ice forms a fan-shaped mass at the foot of the mountain range.

3) Alpine Glaciers: Also known as hanging glaciers, these ice masses start high on the slopes of mountains, and literally ran from the mountainsides.

We also learnt that the areas

surrounding our journey are habitat for more than 1645 animal species, some of

the important species being: Sea otter, Harbor seal, Ribbon seal, Stellar sea

lion, Black-legged kittiwake, Eagle, Black bear, Mountain goat, Dall’s

porpoise, Orca/Killer Whale, Humpback whale and Minke whale.

The journey on the cruise was

exhilarating. It was a great experience standing on the deck outside the cruise

ship, and facing the strong wind. We saw glacier after glacier, otters, eagles

and many more. Lunch was provided in the cruise and it was just okay. When the

journey was about to end, the Forest Ranger who was conducting the tour

gathered all the small children, administered a pledge to all of them and

presented a Junior Forest Ranger Badge to every one of them. Sanjay was once

again very proud. We were back at the harbor at 05.30 PM. We, immediately,

rushed to our vehicle to get back through the tunnel and drove all the way to

Talkeetna, north of Anchorage, on our way to Denali National Park, our last

destination in our Alaska tour.

………..to be concluded in Part V